Atomic SRS

Atomic SRS

Almost everything there is to say about how to make cards has already been said. See Peter Wozniak’s 20 rules of formulating knowledge for general tips, Michael Nielsen’s long post on using Anki, and Gabriel Wyner’s Fluent Forever for language-learning tips.

Instead of saying what has already been said, I’ll make a few comments about how to begin with an SRS. How to apply the idea of “atomic workflows” to building up an SRS practice.

I’ve been using Anki for a long time, so I may not be the best reference for starting an SRS practice. But——I did fall out of the habit for most of 2019, and having to relearn the routines gave me a few ideas that might be useful to real newcomers.

Habits of an SRS

The atomic workflows process begins by identifying the basic habits that build up a workflow, reducing that set to the most essential subset, then reducing those habits to their fundamental actions.

An SRS workflow comprises three habits:

- 🔄 Reviewing cards (once a day)

- 📥 Gathering content (continuously)

- 🏷 Making new cards (once or twice a week)

Of these, the first is the most important to long-term memorization, and it’s where we’ll start.

Reviewing Cards

And a Note on Using Other People’s Decks

At some point, you’ll hear the advice to avoid using other people’s flashcard decks. It’s good advice: when you create your own cards, they’re more personal and ultimately easier to learn. But you can break the rule when the deck is predominantly visual and when its cards are totally irreducible.

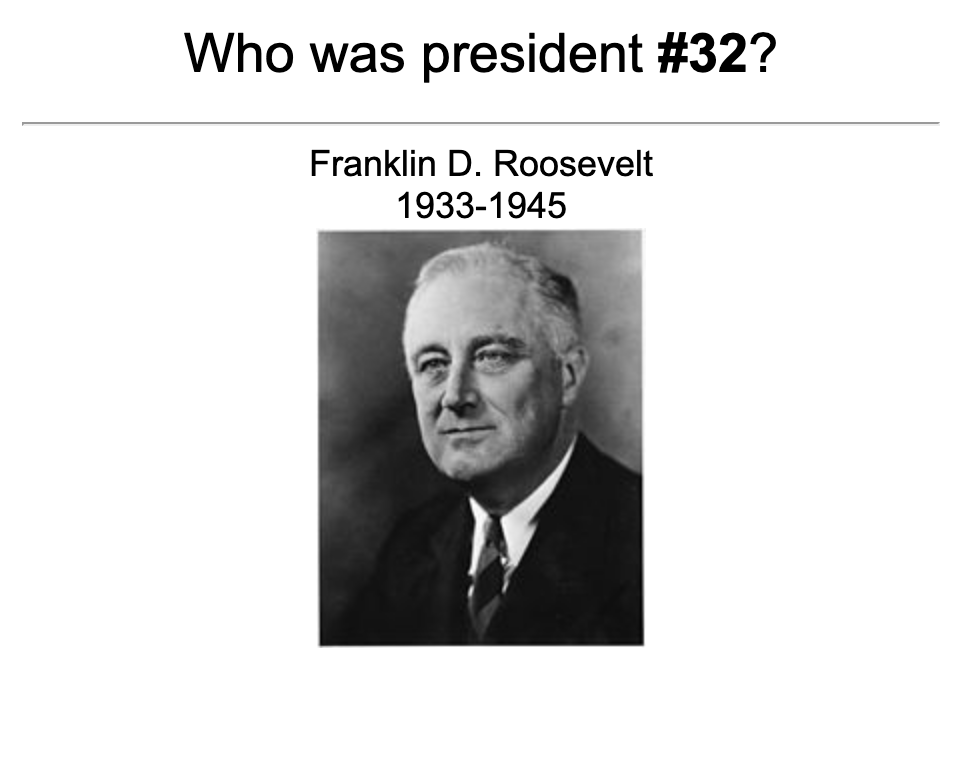

The most obvious examples of acceptable deck-stealing are in subjects like geography (e.g., countries and capitals, US states and capitals, German provinces) anatomy (e.g., bones, muscles), and occasionally history (e.g. US presidents, art history, Egyptian gods).

Cards to steal

But do not use other people’s decks for subjects like languages (where other people’s definitions and translations mislead) or science and history if you still lack the big-picture understanding (let me point out that Wozniak’s very first rule is to understand before you memorize). Otherwise, the cards won’t fit you.

Besides the risk of impersonal cards, another risk in using other people’s decks is that their cards are simply bad. The cards may demand too much information, provide too little imagery, or end up irrelevant. So tread carefully and refer back to the 20 rules.

Cards to avoid stealing

How are you going to know that I meant “hood” with this picture and not “hoody” or “shady” or “delinquent.”

Probably not a great card of mine, but how are you ever to guess that I prefer this answer over “to provide early evidence of oxygen and carbon dioxide” or “to provide evidence of photosynthesis and respiration.” And you won’t know any of these broader implications if this card is your only exposure to the subject.

Still, for the newcomer I recommend starting with a shared deck that meets the “obviously appropriate” criteria above.

Choose a fixed moment of your day (for me it’s the last part of my morning routine) to build the habit of a daily review session. Don’t worry about raising the number of cards you introduce per day—just keep the review short enough that you’re able to it consistently.

Tip: except for foreign languages, group all of your cards together under one parent deck. This way you’ll train a memory resilient across different contexts.

Avoid languages and avoid making your own cards. Whatever your end-goal, there’s almost certainly some bit of trivia you’ll find amusing enough as detour. Build the habit first because the daily review is the most important part of the practice.

Falling behind: If you stop reviewing your cards for only a few weeks, you can rack up hundreds or even thousands of backlogged cards. To recover use the same principle as you would when first starting: cap the number of cards you review per day so you focus on consistency over flux.

Making Cards

Next in importance after reviewing cards is making cards (so you can start to learn more than just geography and anatomy). I put aside one hour a week for Italian and one hour a week for general information. You probably won’t need more than this.

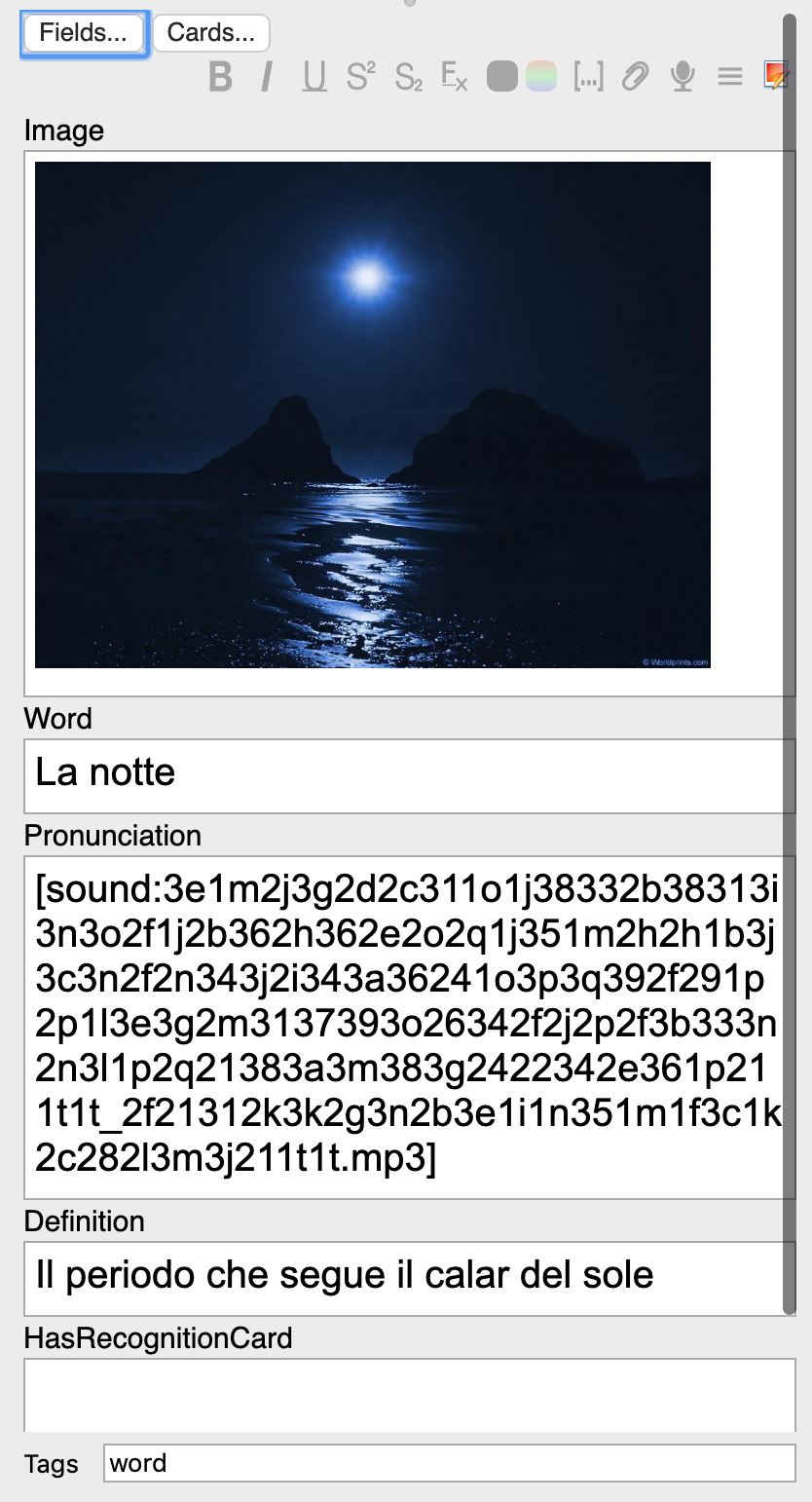

So you’re ready to start making cards. First, familiarize yourself with Wozniak’s 20 rules. Then, establish a fixed moment every week (maybe right before or after a weekly review) for making cards. For the time being, keep it simple. Restrict yourself to the following note types: basic, basic and reversed, and cloze deletions.

As for gathering content, choose an easy subject. Something that lends itself to lists. E.g.: vocabulary in your native language, local bird species, or notable political/royal figures.

Basic provides a question and answer

Basic and reversed is useful for word-pairs to train both active and passive memory.

Cloze deletions are useful for smaller items in sentences (also for grammar in a language).

Don’t play around with creating your own note templates until you’re intimately familiar with these basic types. And if you do want to explore this avenue, finish reading the Anki documentation first. More often than not, you won’t need anything fancier. If you want to learn a language, this is the stage to start dabbling with Gabriel Wyner’s strategies in Fluent Forever (and, if you’re interested, he’s built a new app that might be worth looking into).

Example from Gabriel Wyner’s Arabic pronunciation trainer.

Gathering Content

With [[GTD]], you need an inbox where you write down your thoughts before expanding them into tasks then moving them to their relevant horizons. With the [[Zettelkasten]], you take fleeting notes before converting them to permanent notes. So too, with an SRS practice, you need a place to gather questions before converting them to cards in your weekly card-making session.

The easiest starting point is the unassuming list. For example, with physical books I use a post-it as a bookmark that I fill with new vocabulary. With Italian I return to a list of Kindle highlights from my reading and to a separate list of feedback from my weekly speaking practice. With research articles I use variants of the Cornell note-taking method: the questions in the side column immediately translate to questions in Anki.

Consider my examples as illustrations not prescriptions because this habit offers the most flexibility of the three. So use trial and error, and see what sticks.

My next step is to migrate to keeping these lists in Obsidian. Then, to incorporate the Obsidian to Anki plugin. Indeed, the similarity between all these workflows points to a possible unification, but that will have to wait until a future post.

Conclusion

To adopt an SRS workflow, begin by cheating: steal another person’s deck to build your daily review habit. Only then move on to making your own cards. Start with simple note types and expand from there. As for gathering content, use simple lists.

In the future, we’ll explore fancier integrations with other workflows (GTD and the Zettelkasten), so stay posted.