Feed

Memorizing sequences

This is the third part in a four-part series on memorizing statistics. Here, we focus on memorizing sequences.

- 1 Projects/Writing/02 Series/Memorizing/Memorizing numbers (start here)

- 1 Projects/Writing/02 Series/Memorizing/Memorizing units

- 1 Projects/Writing/02 Series/Memorizing/Memorizing sequences (you are here)

- Memorizing sources (to be written)

Throughout the series, we've been building on top of a spaced repetition system (SRS).1 That's because—whatever the subject matter—memorizing requires repetition, and our drive towards efficiency (read: laziness) means we want to minimize the frequency of repetition. Enter the unreasonably efficient SRS.

With an SRS memorizing becomes a choice. You just deposit a nugget of information in your deck of flashcards, and the information will eventually come to rest in your long-term memory banks. Usually.

Sometimes, getting a bit to stick requires more effort. Such was the case with with numbers (start of this series) and units (part 1) because these types of data interfere. When you attempt to deposit 18.6% in your mental bank, you're liable to withdraw 16.8% or something altogether different.

For numbers, the solution was to use mnemonic techniques like the part 2. These hijack our strong visual machinery to separate numbers out of interference's reach. With units, the solution was to avoid memorizing as much possible. Instead, to develop a physical intuition that would make the units self-evident. And when that fails, to use Major system.

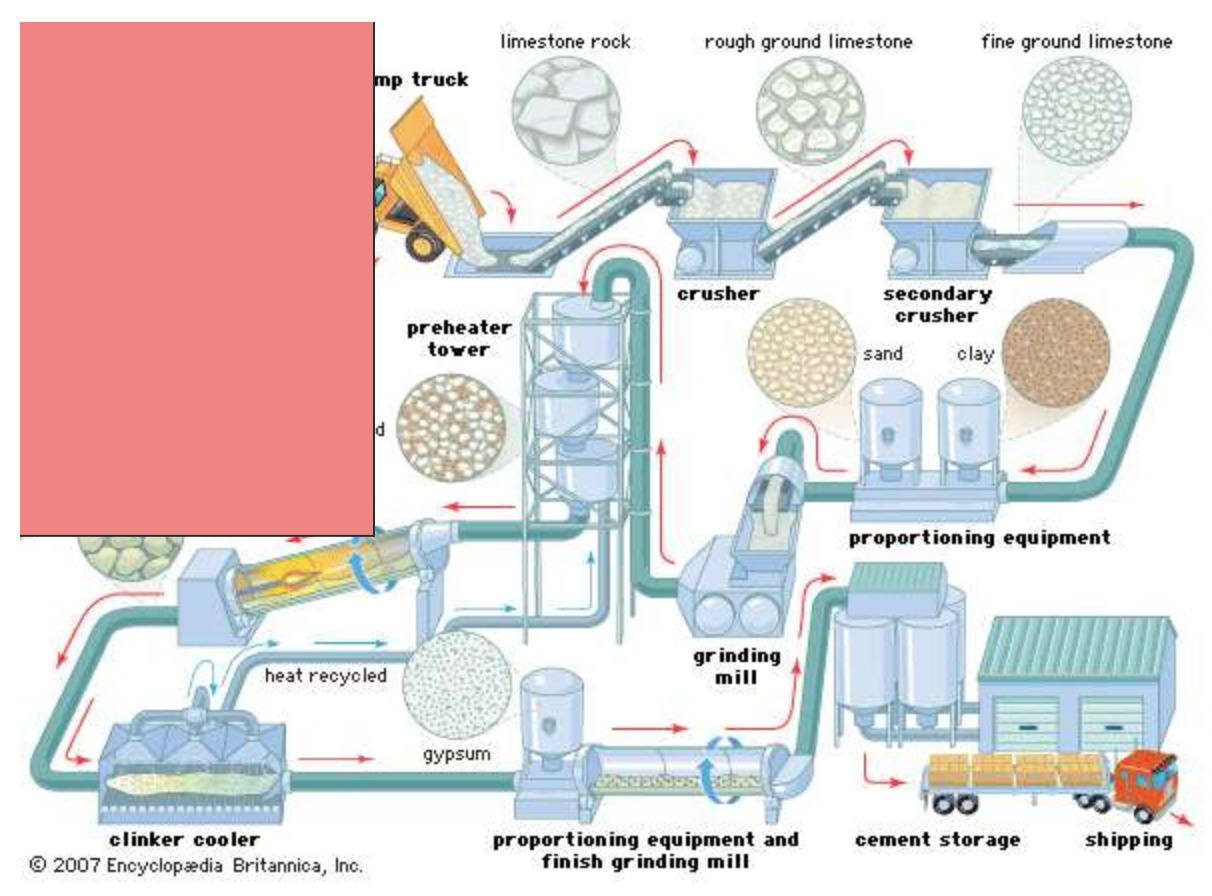

Here with sequences, the difficulty is elsewhere: a sequence presents too much information to recall all at once. Suppose we wanted to memorize the stages of the cement-manufacturing process:2

Cement manufacturing

- Mining raw materials: limestone, clay, sand, & slate

- Crushing and grinding hard materials; Stirring of soft materials

- Blending in right proportions

- Burning in a kiln to produce "clinker"

- Grinding the clinker with gypsum

Naïvely, we could put this on the back of a flashcard and write something on the front like, "what are the 5 stages in the manufacturing process of cement"? But flashcards are supposed to be atomic. As cards get larger, the odds that we forget one item increase towards certainty. Big cards are bad.

Fortunately, we have better options.

1. Break it Apart

The first thing we could do is to divide the sequence of 5 stages into 5 different cards:

What is the first stage in the manufacturing process of cement? […]

What is the second stage in the manufacturing process of cement? […]

With simple examples, this may be more than enough. But this approach hides several weaknesses.

First, with a sequence, we often care more about relative order than absolute order. Say I forget whether "clinker" is what goes into the kiln or what comes out of it. I'd have to call to mind stage 4 and stage 5 separately then compare their abstract ordinals to resolve my confusion. Better to skip the labels and learn directly that grinding clinker follows burning in the kiln.

Second, your choice in labels might not be universal. Two different people could disagree about how to classify the stages of cement manufacturing (maybe mining & extraction fall outside of "manufacturing"). A third might expect more granularity in your description.

Finally, reducing a sequence to numbers again risks the interference effect. You might accidentally swap two steps in your head.

2. Use Overlapping Cloze and Images

With a little extra effort, we can get around these problems.

To emphasize relative order over absolute order, use overlapping cloze-deletions (i.e., fill-in-the-blank). Rather than prompt each step in isolation, provide the previous or surrounding steps as context. Check out this Anki plug-in to make overlaps easier.

What is the next stage in cement-manufacturing?

- …

- Crushing and grinding hard materials; Stirring of soft materials

- […]

- …

- …

- …

- Crushing and grinding hard materials; Stirring of soft materials

- Blending in right proportions

- …

- …

Better still to shift to images so you can take advantage of your visual and spatial brain powers. Use the Image Occlusion Enhanced plugin (by the same author) for the visual equivalent of cloze-deletions. Hide part of a sequence diagram and prompt yourself to fill it in. Not only is this often easier to memorize, but you avoid the risk of "locking-in" too rigid a sequence: with a picture, you can always add in additional intermediate steps later.

What is the first stage in cement manufacturing? memory pegs

1. Mining raw materials: limestone, clay, sand, & slate3

3. Use Memory Pegs

What if the sequence we're trying to memorize is intractably numerical. Then, how to avoid interference?

Suppose we wanted to memorize the order of the biggest emitters of CO2 (from WRI 2020). And we have to know the explicit rankings. 4

GHG emissions by country

- 🇨🇳 China: 11.8 GtCO2e

- 🇺🇸 USA: 5.77 GtCO2e

- 🇮🇳 India: 3.36 GtCO2e

- 🇪🇺 EU: 3.20 GtCO2e

- 🇷🇺 Russia: 2.46 GtCO2e

- 🇮🇩 Indonesia: 2.28 GtCO2e

- 🇧🇷 Brazil: 1.39 GtCO2e

- 🇯🇵 Japan: 1.24 GtCO2e

- 🇮🇷 Iran: 0.882 GtCO2e

- 🇰🇷 South Korea: 0.671 GtCO2e

Now, you could use the technique we explored in  (the part 1) to memorize the amount of emissions.

(the part 1) to memorize the amount of emissions.

E.g.: to convert 11.8 GtCO2e into letters ("TTF") then into words ("too tough") and make a mental association (China becomes an impassive bouncer). But we care about rankings not absolute terms.

If we try to apply the Major system to the single digits of a (short) list of rankings, the technique breaks down. It's difficult to make sticky words & images when you have only one letter to work with. E.g. 1st -> "T" -> ?, 2nd -> "N" -> ?, etc.

Instead, we're going to use perhaps the simplest mnemonic technique: the memory peg. Ahead of time, we associate an object (a "memory peg") to the ten (or more5) numbers we'd like to be able to memorize.

To make it easier, a common choice is to make the initial association by rhyme or sound.

Memory pegs

- One -> Gun

- Two -> Shoe

- Three -> Tree

- Four -> Door

- Five -> Hive

- Six -> Bricks

- Seven -> Heaven

- Eight -> Plate

- Nine -> Wine

- Ten -> Hen

We actually already saw this technique in Major system, where we created a memory peg for each unit we might want to remember. This is the same idea but for numbers. And it makes sense to use whenever your numbers are single digits. Moreover, you can use this technique in conjunction with the previous techniques.

Then when it comes to memorizing the numbers, we instead make an association with the memory pegs.

E.g.:

- 🇨🇳 China: I'll leave it to you to make an association between China and guns, violence, genocide. Very difficult.

- 🇺🇸 USA: How about imagining Trump leading a ritual burning of Nike shoes because of Colin Kaepernick while the QAnon shaman dances over the flames.

- etc.

When we get past 2 digits to memorize, it's natural to graduate to the part 2. In either case, you'll still want to prompt yourself with flashcards you've made on Anki.

4. Use a Memory Palace

If you need something more powerful, you can use a memory palace (aka "method of loci").

The premise is simple. Visualize a place you know well. Then, mentally fill this location with the items you'd like to memorize. Move through the location (in your mind) and pass the items in the order you'd like to retrieve them. It helps to make the items as grotesque and lewd as you can.

Our brains are highly adept at visual and spatial reasoning. The memory palace hijacks this ability to store potentially incredible amounts of information.6 It's the foundation for the strong memories of professional mnemonists and indigenous communities the world over (Kelly 2019).

In my personal experience, I don't end up using the memory palace often because I find it requires too much time compared to the other approaches (at least for simple sequences and non-prose). This is probably more evidence that I am a novice mnemonist than that the memory palace is excessive (professional mnemonists can memorize decks of cards using memory palaces in minutes7). With more experience, the time it takes will go down, but the benefits will remain high.

But until we novices get to the level of expert, simpler techniques have more than enough to offer. They bridge the gap and keep us motivated at our growing memories as we develop yet better techniques. (2 Areas/Principles/Laws/Benford's law)

Conclusion

Try it all, and see what works.

Footnotes

Footnotes

-

Specifically Anki though you can use whatever you want. Point is: I'm assuming familiarity with the idea of an SRS. If that's not the case, return to the Major system. ↩

-

My examples throughout this series remain tied to the climate crisis. As it turns out, cement is responsible for 4-8% of global CO2 emissions (Britannica 2021). ↩

-

We should probably further split "limestone, clay, sand, & slate" into their own set of flashcards. ↩

-

This example is a bit contrived since rankings change all the time, but the point is to demonstrate a mnemonic technique. ↩

-

Because of 1 Projects/Writing/02 Series/Atomic Workflows's (which states that the leading digit in natural sources of data tends is "1" disproportionately often), it makes sense to come up with memory pegs for all numbers between 0 and 20. Additionally, you can come up with memory pegs for the letters in the alphabet then track orderings by letter. You'll manage up to 26 items (at which point you can safely return to the top and repeat). ↩

-

Using pictures gets us part of the way there, but it still limits us to only 2 dimensions. ↩

-

I haven't mentioned Person-Action-Object (PAO), which is a subtechnique of the memory palace that many professionals use to memorize long sequences of digits and playing cards. Maybe it serves as practice, but I feel PAO is a little too contrived for what we need in real-world memorizing. Knowing the digits of to the thousandth decimal is not going to make you a better conversationalist or debater. ↩

The transience of health science

One of the challenges with 3 Resources/Concepts/Health is that the science seems to change constantly. Animal fats were fine, then evil, and now okay again (read: the holy of holies if you're in the keto cult). Breakfast was the most important meal of the day until the intermittent fast took its place. Coffee caused cancer, cured cancer, and who knows what it does now. We were supposed to avoid exercise to preserve energy. Now, if you don't exercise, you're pretty much committing suicide by attrition.

So too with Sleep. Neuroscientist Matthew Walker's Why We Sleep is one of the more recent examples of popular-health-science-gone-viral. The thesis is that we should be getting more sleep. Sounds reasonable enough.

Quackery

Only it turns out that the book may contain a host of erroneous claims. Most interestingly, the sacred eight hours a night may be a myth. You might be able to get by fine with seven hours or even six hours. Now, if you've been sticking to the recommendations like I have, two additional productive hours a day would be life-changing. It could mean years of being awake added to an already short existence.

But they'd better be "productive". And I don't want to be the fool hopping from trend to trend at the whims of popular opinion only to have to swing back to eight hours when that again becomes fashionable. Especially when health science in particular is so fickle. How are we outsiders, too busy to go into the primary literature ourselves, to judge these claims?

Null hypothesis

First, the evidence of absence deserves greater credibility than the evidence of presence. In complex systems (like the human body) it's difficult to come up with anything that looks like a clear one-sided correlation.

So a scientific1 claim that the amount we sleep has a definitive causal relationship with mortality and cancer risk warrants greater skepticism than the scientific claim that sleep has no consistent effect in any yet-observable way (source). At least within some reasonable bounds (say 6 to 9 hours).

Walker, true to scientific heritage, took the time to respond to his critics. He reviews a host of studies that point to 6 hours really being too little: it's bad for your reaction time, your risk of diabetes, certain cancers, cardiovascular disease, your all-cause mortality, etc. Sleep is important. Still, his book has enough sloppy mistakes that we should somewhat discount the bolder claims.

Ultimately, we don't know what the ideal amount of sleep is per individual. And that's really where the fundamental challenge with health science lies. Individuals vary. A lot. What works for me need not work for you. And when the scientific method requires us to study large groups, we work with averages that may not be representative of any one individual.2

The solution is to treat yourself as test-subject. Try a bunch of different things and see what works. Space your experiments across time to recover a semblance of the scientific cornerstone of repeatability. It will never be as rigorous as the experiments in a particle accelerator or gravitational wave detector, but we don't need the same 5-sigma significance for our investigations to yield a positive effect.

The promise of the rather hype-y fields of "behavioral health" and "personalized medicine" is to make this tinkering more accessible. To make it easier to track important metrics and automate the analysis so that everyone can become the experts of themselves. If we can deliver on that promise, well, then good health need not remain the sole dominion of the elite and wealthy.

Don't mindlessly chase all the latest health trends. But also don't let the variability of health science become an excuse not to listen to new findings. Let scientific literature, old and new, serve as a starting point for your own investigations into yourself. Find what works for you, and keep on experimenting.

At the end of it all, I've learned to be less of an 8-hours-a-night zealot. And to explore a wider range of times to see what works. For now, that's enough of a lesson.

Footnotes

Footnotes

-

I.e.: backed by experimental and observational evidence. ↩

-

For example, flip an unbiased coin, and average what you see. Heads = 0; Tails = 1. In the large number limit you'll approach 0.5, which is not equal to any individual sample. You can take the mode, but this will alternate between 0 and 1 infinitely many times. And if you have more options or continuous options (as is the case with most health metrics), the mode becomes uninformative or ill-defined. ↩

Introduction to the 48 Laws of Cooperation

I just finished Robert Greene's notorious 2 Areas/3 Notes/3 Sciences/0 Mathematics/AM3D Axioms, postulates/48 Laws of Power/48 Laws of Power.

The book is exactly what it sounds like: a guide to acquiring power in 48 easy steps. It's a self-help-book-meets-historical-medley that makes for an engaging albeit cynical read— everyone's out for themselves, and it's dominate or be dominated.

No surprises, the book has become a cult classic among hip-hop artists, and entrepreneurs, but also prison inmates and domestic terrorists. Now, these less-than-reputable associations may lend the book an exciting bad-boy appeal (Law 6), but, at the end of the day, popularity among criminals also hints at some kind of defect (Law 10).

Don't get me wrong, I loved the book (if only for the historical examples), but Greene's theatrically nihilistic worldview gets a few key things wrong. I thought I'd point those out, and offer an antidote in what I'll call, 1 Projects/Writing/02 Series/The 48 Laws of Cooperation/The 48 Laws of Cooperation

1. Power is a weak end

First, power is not an end but a means. You can tell your audience to always keep "the end" in sight (Law 47), but if you don't teach your audience which goals to aim for, power becomes its own end. You end up proselytizing a cult of power that leaves us all weaker.

Instead, power needs a purpose that goes deeper than saturating one's need to believe (Law 27). Power is a tool to work towards your own well-being (and, if you're feeling generous, the well-being of those around you). Only the most thoroughly psychopathic can extract well-being directly from power. For the rest of us, our most reliable and profound sources of well-being often require us to willingly give up power1 : to do things for others, to open up and be vulnerable, and to efface the ego.

If you're not using your power to help the people out of power—to make the game more immune against the power-hungry—you're a sad, unenviable douchebag.

2. Power is an incomplete lens

Second, power is not everything in human interactions— not nearly.

With power, interactions become a zero-sum affair: dominate or be dominated. The vulnerability is that this lens is self-affirming. If you seek power, you surround yourself with power-hungry competitors who confirm your cynical suspicions and, in turn, their own.

The most interesting (and complex) interactions have less to do with power, and they are not nearly so minimax-able. These situations are closer to Prisoner's Dilemma's: You and your "opponent" are equals. Your interests are almost aligned but not quite. Cooperation is in sight but, unless you put in the extra effort, no guarantee.

The power-hungry cynic will choose defection as soon as it becomes strategically favorable (Law 13) because they cannot imagine their opponent acting any other way (or if they can, they disparage the opponent as a "sucker" to be taken advantage of; Law 33). In the long run, such a strategy will leave your community fragile, its members wary and distrusting, and you alone in all existence.

Just try it. Try the 48 laws out on your kids. You will be estranged before they leave the house. Try it out on potential partners. Yours will be a string of unhappy flings. Try it out at work. "Friend" will be an abstract dictionary definition without any foothold in your world. You may be the greatest actor and deceiver (Law 3) of all time, but you can't stay (or want to be) impenetrable to those closest to you. And eliminating all your emotional intimates is a self-evidently imbecilic move (Law 18).

3. History remembers the lucky

Third, Greene gets to cherry-pick the greatest power-seekers in history. But the stories of most of those who tried and failed don't get written. If you try and follow the greats, odds are you will end up with the rejects. If you view the world as you-against-everyone-else (which is the cynical result of all the power worshiping), the numbers will be on your opponents' side. You will lose (and maybe end up in prison worshiping the book whose mentality got you in this mess).

Better to cooperate than to defect. Your best chance at both security and well-being is to side with a community that looks out for you. When you willingly sacrifice your individual power for the good of those around you and they reciprocate, you will be infinitely more powerful than you could ever have been in a group of self-interested megalomaniacs.

Listen to Seneca: "If a thing is in your interest it is also in my own interest. Otherwise, if any matter that affects you is no concern of mine, I am not a friend. Friendship creates a community of interest between us in everything. We have neither successes nor setbacks as individuals; our lives have a common end."

Greene gets a little closer to "cooperation" with his other book, The 33 Strategies of War. But it remains the perspective of the general, the man above and beyond his fellow soldiers. It can be lonely up there.

Like power, cooperation is no guarantee. It takes work to realize; you have to follow rules and principles— say about 48 of them.

In the coming weeks, I'll be releasing my antidote to Greene, 1 Projects/Writing/02 Series/The 48 Laws of Cooperation/The 48 Laws of Cooperation, in serial form. Sign up to stay tuned.

P.S. In Greene's defense, his book is not as unrelentingly cynical as I paint it to be. Obviously, cooperation has a value to the power-hungry. Call me a romantic, but I just don't agree that power stands above cooperation. In fact, I think this mentality is one of the deadly diseases of our time and place.

Forgive me where I exaggerate. Then again, Law 6 and Law 42 tell me a good way to gain attention is to attack a well-established person in power. Today, that person just so happens to be you, Mr. Greene.

P.P.S. Greene accuses those who claim they are outside the game of power to be lying (or to be ignorant). That those who make an appeal to equity want to parcel out the resources myself. No, my appeal to equity does not mean that I want to be the one to redistribute the power. Despite all of its failures, democracy remains our best solution to that. But yes, I'm sure that being seen as generous and liberal (in the classic sense), i.e., signaling my virtue, is one of my motivations for writing about cooperation. Again no, my demonstration of honesty in revealing this motivation is not designed to gain more brownie points. Then again, this whole meta-self-referential analysis probably is.

Footnotes

Footnotes

-

Actually making sacrifices — not just making the appearance (Law 22). ↩

Day of maintenance

Day of Rest

Many cultures observe a "day of rest."

Though often packaged in mawkish religiosity, these days of rest have something to teach even the most fundamentalist secularists among us.

But we already know that. For the body, we take rests days to prevent injury. For the mind, many productivity-zealots dabble in dopamine fasts and daily meditations because creativity and self-awareness require a balance of focused thinking and diffusive thinking[^1]. We can't get to diffusive thinking without undirected time for reflection.

Still, at least for me, the idea of dedicating one day a week to doing nothing sounds a little extreme. As far as I can tell, I don't have a spiritual void to fill with the a weekly church service, and my daily moments of pause—in meditation, meals, and walks—are currently enough to prevent mental collapse. Why sacrifice time that I could be doing something?

Day of Maintenance

Instead of a day of rest, then, I propose a day of maintenance. If you're anything like me (and, I wager, most humans), you're liable to suffer a severe case of novelty bias—constantly starting new projects without finishing what you've already started. 1

On a day of maintenance, you'd curtail content creation (be it in writing, programming, researching, painting, composing, etc.). Instead, you'd maintain what you've already begun. E.g.: cleaning up your Zettelkasten, trimming your GitHub repos, maybe writing the documentation and tests you've been putting off, organizing your references, managing your GTD and email inboxes, and conducting a weekly review.

Moreover, you can easily combine it with your more mundane household chores: vacuuming and tidying, washing your clothes, or doing a groceries haul.

Especially when a pandemic and lock-down threaten to turn your every day into a copy of every other, a day of maintenance, rest, or "the lord" might be just the thing that restores your control over time. And maybe if we all spent just a little more time on maintenance, there'd be just a little less crap out there: less garbage code, out-of-date libraries, repetitive apps, and disappointing platitudes. So get maintaining.

Footnotes

[1]: Aka system one versus system two thinking or the default mode network versus task-positive network.

Footnotes

-

Right after I finished my first draft of this piece, I found Cody McLain's The Importance Of A Maintenance Day And Why You Need One. Like always and everywhere, it's impossible to be original. Even in presentation. Oh well. ↩